Michelangelo once said:

“Trifles make perfection

but perfection is no trifle.”

A few small details can lead to long strides on becoming a better writer. Tried and true tenets—show don’t tell, limit adverbs, use (or don’t use) dialogue tags, active voice not passive voice—are all familiar to most writers. They come easily to the tip of the tongue—though not so easily to the tip of the pen—but all are valuable.

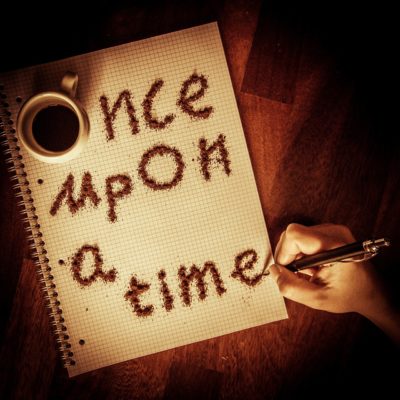

Another maxim that serves the writer well is to engage the reader’s interest early. If you lose readers in the first chapter, they will never get to enjoy the way you master your craft.

The first pages of a story are all important. It is imperative to lure the reader into the story. The quicker the better.

Powerful first lines dominate great novels:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” — Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

“Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.” — The Stranger by Albert Camus

“The Man in Black fled across the desert, and the Gunslinger followed.” — The Gunslinger by Stephen King

“Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn.” — The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

These potent first lines beckon the reader to turn the page. They propose a mystery and promise a solution.

Jeanne Leiby, who served as an editor of The Southern Review at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, had a simple and effective message:

“The story starts after the telephone rings, after the knock on the door.”

As demonstrated by dynamite first lines, potent beginnings are devoid of back story. A sure way to lose readers is to bog them down with minutia that can be woven into the story at a more opportune time. Non-essential information produced in the beginning can confuse the narrative and dilute the impact of what otherwise might be a powerful introduction.

That being said, however, a tidbit of information about the character’s “receiving the call or answering the door” can add to the impact of the story.

As authors, we want the reader to be invested in our characters. A few sentences can give the reader a peek into the temperament, disposition, or condition of the individual and a reason to be interested in the character’s future. Which, of course, is on the next page.

While cluttering the first pages of a story with minutia is a recipe for disaster, failing to place the reader in time and space in your novel can be just as detrimental. A reader doesn’t want to read ten pages only to see a line that places the story in nineteen fifty when he thought it to be contemporary. You can ground a reader by including a chapter heading or page break with a note of time and date. A more subtle device is to include, early on, an anachronous line such as, “John placed a nickel in the coin slot and dialed ….”

It doesn’t matter how you go about doing it as long as the reader knows the time and place of the story.

Then lure the reader in with a sense of conflict to come. Conflict is the life blood of any story. Without a challenge—whether it is a mountain to climb, a mystery to solve, or family in crisis—there is no story.

Thomas Paine penned in his pamphlet Common Sense the line:

“The harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly; it is dearness only that gives everything its value.”

Paine, of course, was referring to the politics of the day. However, we can take his words and apply them to our craft. And as Paine implies, the more arduous the conflict, the greater the protagonist’s triumph (or defeat).

So get into it early. Once invested in the character and conflict, your reader will want to turn the page.

Wendy Thornton

Great advice here. Especially these days when we have so many options, it’s important to draw the reader in right away.

Rick Sapp

Nicely written, Frank! We didn’t know you knew the word “anachronous!” Brilliantly done.

Frank Fioralisi

Thank you Wendy and Rick. You’re correct Rick. I didn’t know I knew the word “anachronous” !!

Art Crummer

Excellent article with solid advice; and true enough for nonfiction (including certain types of history), creative memoir, and especially short fiction. Thanks for a succinct, accurate synopsis.

BTW, doesn’t ‘anachronous’ mean poems written by or about spiders or snakes? 🙂

mallory oconnor

Enjoyed the good advice and the fine examples. Got me re-reading my “first lines.”

And Art, you must be thinking of “anacondious” or “aracnophobius.”

Joan H. Carter

Such good advice! I need those reminders. I know better, but I must remember that the reader doesn’t have to know all the background in the first chapter. And in writing memoir, I tend to lose myself in my past environment (dial telephones and telephone booths), forgetting that the reader lives in a today’s different world.

Kylie Brandon

Such an informative and good article. you give very advice. It helps a lot. You did a great job. Keep it up.