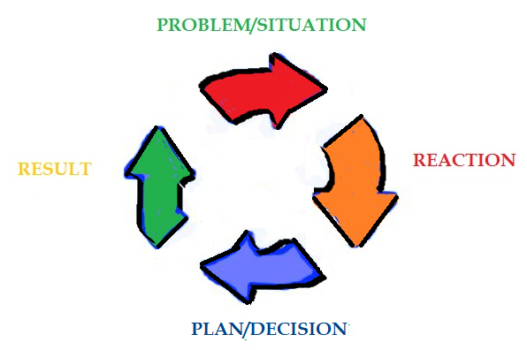

Some years ago, I took an online mystery-writing class. The one helpful takeaway for me was what I’ll call the Wheel of Tension, which moves the plot along. This is not limited to mystery writing; it works for all fiction and non-fiction. The Wheel of Tension is this: A situation or crisis arises, the character or characters react, some determination is made about how to resolve the situation, and then that plan is put into place. Oftentimes, the solution to the problem sets up another situation, and the wheel goes around again and again.

This seems so ordinary and intuitive as to be hardly worth mentioning, but as a beta reader and pod member, I’ve noticed that without these components, specifically reaction, a good story can feel flat. It can be reduced to a list of events. I had lunch, I went for a drive, I got into a car crash, I went to the hospital, I couldn’t call my family because I was in a coma …

This could be a gripping and emotional story, but it lacks oomph and emotion and reads more like a honey-do list:

- wash the dishes

- vacuum

- mow the lawn

- walk the dog

- clean the gutters

Yawn.

The reaction part is essential. If we skip the reaction, we skip an essential opportunity to engage and inform the reader. And it won’t feel right because, in our own real-life experience, we go through this wheel all the time. Problem: Someone says something hostile to me. React: Whoa! I’m feeling attacked! Plan: How am I going to respond? With anger? Walk away? Try to diffuse the situation? Result: Does the situation escalate? Does the person follow me? Does the person apologize after my explanation? Do the police get involved? This may set up a whole new situation.

Let’s work with the situation of a multiple-car wreck where the narrator is only mildly injured. A normal person would react with shock, fear, horror, concern for others, perhaps a feeling of helplessness or of being overwhelmed, not knowing what to do. If the narrator is a psychopath, however, he may react with anger at being delayed. He doesn’t care a fig about others; he’s late for his appointment. The total disregard for the well-being of others is disturbing and sets up a distaste for the narrator.

Let’s do the same scenario with a medical professional as the narrator. The reaction to being in a car crash may be calm and methodical, assessing and then jumping into action to help others. Now our narrator is heroic, and we as readers can focus on the rescues. We would support the character. Yes, save lives! Save lives! Yay! Go!

What if the narrator has hemophobia, the fear of blood? This person would be paralyzed by fear of seeing blood on him or herself as well as on others. Now we as readers may feel the narrator’s fear, but perhaps also frustration that the narrator should be doing something to help others and is instead cowering and having a meltdown. Come on! Pull yourself together! Call 911! Go help the guy who’s yelling! You are fine; go help someone!

In each case, the reaction tells the reader something about the narrator, i.e., whether they are they kind, compassionate, psychotic, weak, etc. The reaction also informs the reader how to feel about the situation. Are we excited about saving people? Angry at our psychopath? Sympathetic but frustrated by our hemophobe? We are engaged in the situation and driven to find out what will happen next. We ourselves react.

Now we move to the plan stage. The psychopath in this scenario may simply put the car in gear and drive away. The medical person would try to save lives. The ordinary person might call 911 and timidly attempt to help others. The hemophobe would stay put in a high state of anxiety with no plan.

The result for each story will be different, depending on the reaction and the plan. Each part of the wheel turns to the next and keeps the reader engaged and emotionally invested. Otherwise, it’s just a list of events: this happened, and this happened, and this happened. The psychopath got into a car accident and drove away. The hemophobe sat in his car and did nothing. The nurse saved lives. This is not engaging. And we, as readers, have other things we could be doing, like washing the dishes and mowing the lawn.

Kaye Linden

Excellent article. Yes. Each scene must have structure and conflict with reactions that advance the story. Thanks for writing this with great examples to illustrate your points. Kaye

Terri Depue

Great post Jess. This is useful information for writers at all levels. An excellent reminder with clear examples. Well done.

Mary Bast

Love your style & sense of humor.

Jess Elliott

Thank you, Kaye, Terri and Mary! Thanks for the feedback. I appreciate the encouragement much, as I often get the 3 a.m. staring at the ceiling blues that my fiction-writing is akin to singing in a sound-proofed, Dr. Who-style tardis out in space… it hardly matters whether it’s good or bad — no one is listening!

Glad the non-fiction is enjoyed 🙂

Skipper Hammond

Thanks, Jess, for making writing advice fun to read–like your ghost stories.

Jess Elliott

Thanks, Skipper!