During their writing lives, poets wear many hats. But, at some point, many either become historians, chronicling their time period, or evolve into social activists working toward social and political change.

Still, poets are much more. They resemble an unending string of pearls, members of a unique grouping of visionaries. Each poet glows on their own, and unites with all other poets, joined by common goals: to be both entertaining and thought-provoking. They encourage their audiences to change negative attitudes to positive attitudes, leading to progressive action.

A Little History First

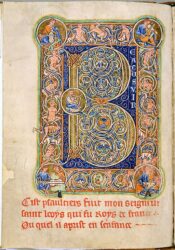

Each generation receives that string of pearls from its elders, creates their legacy, and passes it on to a younger group of poets. Each feels privileged to have received that string, symbol of the calling from those who walked the pathway before them. Most future poet activists were introduced to the power of words from songs and stories told to them as children. Another place of inspiration was at Sunday school, where they read, or were taught, Bible stories. The poetry of Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes sparked a desire to use words as instruments for change.

Most future poet activists were introduced to the power of words from songs and stories told to them as children. Another place of inspiration was at Sunday school, where they read, or were taught, Bible stories. The poetry of Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes sparked a desire to use words as instruments for change.

Psalm 1 advocates social reform as a moral or spiritual decision, requiring wisdom. The psalmist uses a parable, popular usage in Biblical times. A man is given two ways to get wisdom. Jesus would also use parables in his ministry to great effect. The psalm’s most striking metaphor is the bountiful tree planted by the river.

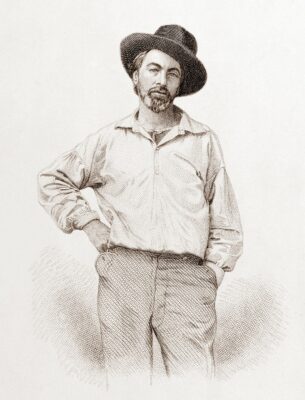

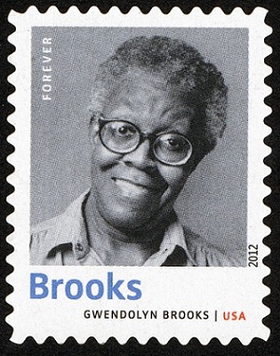

Later, as public school students, these fledgling poets learned of other poets. More refined in their approach to poetry, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Langston Hughes introduced younger poets to a whole new world of possibilities. The more these future activists read the elder poets’ intoxicating words, the more they yearned to make the transition from rough diamonds to glowing pearls in their poetic tradition.

The 1960s and 1970s created a unique time for American political and social activism. Two movements in particular stood out. The Civil Rights movement, which advocated equality for all citizens, and the Black Arts Movement, which championed a national black heritage. Rev. Martin Luther King’s speech, “I Have a Dream,” represents the first movement, while Gwendolyn Brooks embodies the other with her poems: In the Mecca, “To the Diaspora,” and “We Real Cool.”

Whitman and Brooks, Giants Among Activist Poets

And in American literature classes, future poets read the works of Gwendolyn Brooks and Walt Whitman.

Whitman (1819-1892) worked as a journalist, a poet, and a social activist. He loved his country, its people, its cities, and its democracy. Leaves of Grass reflects his life-long passions, serving too as a testament to activism.

Whitman (1819-1892) worked as a journalist, a poet, and a social activist. He loved his country, its people, its cities, and its democracy. Leaves of Grass reflects his life-long passions, serving too as a testament to activism.

Whitman’s “The Great City” asks readers to consider two metaphorical cities as candidates for the title of “Great City.” The first city is known for manufacturing, skyscrapers, schools, libraries, and wealth. However, the second city is known for voting rights for women, the end of slavery, honor for poets and ordinary citizens, and disrespect for authoritarianism, all hot issues during Whitman’s life.

In a similar but very different vein, Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) recorded the experiences of the black community through her poetry. She published her first poem at age 13, and her second book of poetry, Annie Allen, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1950. However, Brooks changed the theme of her poetry in 1967 with the advent of the Black Cultural Movement.

In a similar but very different vein, Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) recorded the experiences of the black community through her poetry. She published her first poem at age 13, and her second book of poetry, Annie Allen, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1950. However, Brooks changed the theme of her poetry in 1967 with the advent of the Black Cultural Movement.

Brookes’s “To the Diaspora” refers to the Jewish dislocation in its title. But she also alludes to African Americans as being separated from their African heritage by slavery and Jim Crow. The poem suggests blacks reconnect to their roots by being proud of their ancestry. She calls this new cultural identity “Afriki.”

And What of Today’s Poets?

Today, many social issues confront poet activists. At the top of most lists, contemporary poets will find immigration, voting rights, climate change, police violence, Covid 19, ethnicity, and gender issues. Creativity and reliable research tools will be necessary.

Modern technology makes today’s poets’ journey easier. You might want to check out some of the following resources:

- The Poetry Foundation offers information on numerous topics.

- The Academy of American Poets, founded in 1934, supports poets no matter where they are in their careers and aims to garner “appreciation of contemporary poetry.”

- Dinty W. Moore shares his often-unconventional approach to writing in various publications. Note that Moore is not a poet per se but imbues his work with poetical overtones.

- Social Justice Poetry’s database of songs, speeches, poems, and historical material deals with social activism of earlier years.

- Split This Rock focuses on social justice and poetry, including a database of social activism poetry.

- Carolyn Forché and Duncan Wu’s anthology, Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500-2001.

Poet activists face challenges every time they sit down to write. They dig deeply for that one great pearl of wisdom that causes humans to sacrifice dearly to possess. Not always successful, these poets continue their quest, using their creativity, personal convictions, and the work of those who’ve gone before.

[Editor’s note: WAG would love to see articles on any and all topics of interest to writers. Please send your ideas or finished pieces to Cynthia D. Bertelsen at BlogEditor@writersalliance.org for consideration. Remember: these posts are more than just posts, for they are actual articles and can be cited in your CV/résumé in the same way you would a short story, essay, or any other writing credit you may possess.]

Mary Bast

I’m delighted to learn more about your background, Leo, and honored that my “Mandala” artwork evoked your poem, “Tangerine Sunrising #1” at GFAA’s Synergy exhibit of art and poetry: https://www.gainesvillefinearts.org/product-page/mandala-mary-bast. I also appreciate your list of resources, some of which were unknown to me.