I’ll admit it, I spend a lot of time compiling bibliographies. For me, there’s something inherently satisfying about seeing a list of references all lined up, like bunches of beautiful flowers waiting to be picked.

Research, for both fiction and nonfiction, requires bibliographies.

To recreate past worlds, as in historical novels, and to understand what historical documents are saying in writing nonfiction books, either overtly or between the lines, you need reference materials, filled with sage advice and insights into the historical times that interest you.

You might ask, “Why should I bother with bibliographies or other books? There’s Google. That’s all I need!”

You might ask, “Why should I bother with bibliographies or other books? There’s Google. That’s all I need!”

Google or Not?

True, Google is a wonder, and you’ll find plenty of material there. But much of what you need will come from sources that you cannot fully access through Google or the internet in general.

And that’s why coming up with a working bibliography is important.

However, compiling bibliographies is a bit like blowing bubbles, for you neither know how big the bubbles will be nor how far away they’ll float through the air.

Or where they’ll land.

And that’s the exciting bit about bibliographies. You can’t know when you set out on the journey where you’ll end up.

But one thing is for sure, and that’s this: You‘ll need a working bibliography to support your quest to recreate the past. Or even the present, for that matter.

Creating Your Bibliography

If you compile bibliographies the old-fashioned way, without resorting to the sterility of database searching, the act itself often turns out to be more exciting than watching an episode of “Forensic Files.” You may not stumble upon murder or mayhem—but you just might, if you read between the lines with the soul of a skeptic. One clue leads to another, until you’re peering at a huge labyrinth of interlocking paths, all leading to the center, the core, the crux of your research.

The recipe for a good old-fashioned bibliographical compilation starts with one basic ingredient: another bibliography, usually in a book highly regarded―that is, cited numerous times―by scholars. Or by other experts in whatever endeavor you’re undertaking.

Where the heck do you find this information?

One way is through a database search of such tools as the Web of Science, the old ISI Citation Indexes, or Elsevier’s Scopus. Libraries usually subscribe to a variety of databases, including FirstSearch and others.

Another, older way is to look at the bibliographies of several books on your topic. If the same books appear over and over, you’ve found your first clue. From that, you can begin choosing references from the bibliography of the most-cited book and go from there. The process resembles the creation of a large family tree. Hunting for information through a database can’t compare to the thrill of running your finger down the page, checking off many references you most likely wouldn’t ever learn of while doing a database search.

Using online databases, while quick, is like shooting fish in a barrel, pretty easy. And you might actually miss a tasty fish or two with online databases.

The keyword here is “indexing.”

Indexing is a process that doesn’t always apply the same terms/tags where they should be applied, given that humans do the initial applying. So, you might find references in your book that won’t turn up when you use your search terms in the database. Even the Library of Congress Subject Headings often fall short.

Again, human error.

So, when you begin to see the same references over and over again, you can be pretty sure you’ve come face-to-face with the basic core bibliography of your topic.

What a joy!

Bibliographies stem from beginnings akin to those of a family tree. They too come to life with different physical characteristics. A simple definition of a bibliography could be described as nothing more than “A list of books.” And that’s just what you see at the back of most books and other works, an immensely long list of books arranged by the author’s last name. Authors often label such a bibliography as “Select Bibliography,” implying that they perused many other sources, but found those sources cited to be the most useful.

Bibliographies such as these, especially if long and ranging on for pages and pages, tend to be a bit useless for the serious researcher of whatever topic is underway. You can’t tell whether or not a certain resource will provide anything juicy for your pot, or paper/book/blog post, if you will. Unless you’re willing to check every single reference, scrutinizing bibliographies for pertinent references can be like panning for gilt nuggets in a cold rushing river: you need to hurry and you might not strike gold, either.

But sometimes such a find crops up. Then you strike a vein of gold ore too good to be true.

Definitions and Formatting

As a quick refresher on the process of creating bibliographies, and why it’s necessary, take a moment to read this clarification from 1916:

As a quick refresher on the process of creating bibliographies, and why it’s necessary, take a moment to read this clarification from 1916:

A bibliography of a subject is to the literature of that subject what an index is to a book. It shows the extent of that literature and the amount of work that has been bestowed upon it. It brings together scattered fragments of book knowledge and makes them readily accessible. Next to having knowledge is knowing where to go for it, and the only enduring guide in that direction is a bibliography.

The most basic of bibliographies is the Enumerative or Subject Bibliography. An extensive subject bibliography, Subject Bibliography covers material about a particular subject and related topics. Generally, you’ll find this type at the back of most books and other published material. It helps you and the reader to annotate or add brief commentary to the entries. But arranging a bibliography by topic can be the next best thing if Father Time is not your friend.

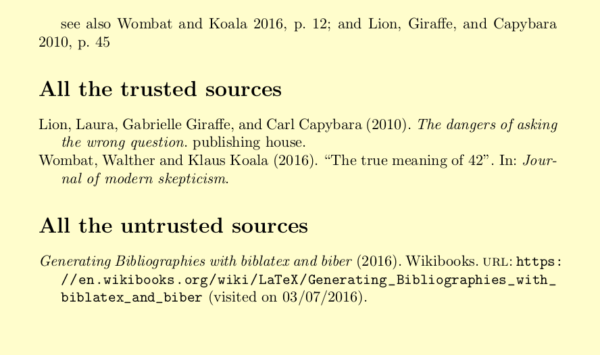

If you include your bibliography in your books or articles or whatever, you usually follow certain formatting styles: MLA, APA, and Chicago. But whatever style you choose, be consistent!

One of the most fascinating, and frustrating, aspects of bibliographies is that they’re never complete. The poor bibliographer often views the bibliography in much the same way that Sisyphus must have while shoving that rock up the hill. Unending.

[Editor’s note: WAG would love to see articles on any and all topics of interest to writers. Please send your ideas or finished pieces to Cynthia D. Bertelsen at BlogEditor@writersalliance.org for consideration. Remember: these posts are more than just posts, for they are actual articles and can be cited in your CV/résumé in the same way you would a short story, essay, or any other writing credit you may possess.]