One of the enjoyable aspects about writing is that it is a lifelong endeavor; there is always more to learn, and sometimes insights come unexpectedly and from unusual quarters.

When it comes to the process of writing a story, I lean more towards being a “pantser” than a “plotter.” Once I envision the beginning and the ending, then the middle usually takes care of itself; not only the action, but the characterization, backstory, the who-what-why-when-how, and so on.

Usually, but not always.

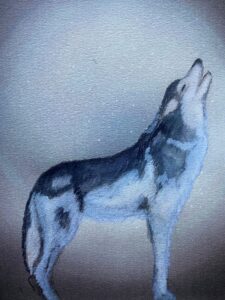

I began a story for my anthology in support of wolf conservation groups howling well. I had a setting (the Viking era), a pair of main characters (Harald the Harebrained and his narrator cousin), a title—Wolfsheart—, a Viking amulet, and had raced off like a wolf in hot pursuit of dinner. Then—

Grinding halt. Brick wall.

Contrary to my normal practice, I’d leaped into action without a vision of the end; I had no inkling where the story was going. And so, to my dismay, it petered out; I’d lost the narrative thread and direction. Frustrated, I tossed it onto the shelf where it languished for a year or more.

Every now and then I’d try to conceive of a solution. Should it involve a Viking saint? (Yes, there were some). Should I introduce a hero from Viking history—Leif Erikson, Erik the Red? How about a sorceress? Bring in more wolves?

Alas, nothing seemed to fit. Rather belatedly, I realized that the basic problem was that I had no idea what the story was about. What story was I trying to tell? Was there a meaning, a point, a message?

Was the story about people or wolves? Heroism or cowardice? Virtue or vice? Love or hate? Loyalty or betrayal?

Was it to be humorous or serious? Feature romance, action, horror or the supernatural?

I didn’t have a clue.

And so it remained until one day I chanced upon an article about wolves which related a revealing piece of information comparing wolves with lions. If a male lion takes over a pride, his first order of business is to kill off any cubs belonging to his predecessor, ensuring that his bloodline is the one to continue.

Wolves, though, are different. If a new alpha male arrives on the scene and the alpha female has pups, the new male, rather than killing them, will protect and provide for them as if they were his own. What matters to wolves is the pack, for the pack is family.

And in a flash, I had the answer to my story—it was about family, both human and wolf. Once I knew that, all the pieces fell into place; I knew exactly where my story was going, and I was able to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion.

Because a story is not like a Meccano set (remember those?) waiting to be assembled—beginning, middle, end, protagonist, antagonist, supporting characters, location, etc., and voila—literary masterpiece! Rather, a story is about someone, about somewhere, about something.

Maybe you have read stories that were mere assemblages of parts (I certainly have!), stories that were not about anything. Competently, even elegantly, written, but ultimately failing to satisfy because they were pointless assemblages of words, structures without heart, empty edifices, hollow shells lacking meaning.

Take it from a wolf—know where your story is going and what it’s about before touching the keyboard. Then you’ll howl with delight rather than frustration.

Connie Morrison

Excellent advice!

Penny Church-Pupke

Well said. Words to live or to write by. Thanks.